We've mentioned this before but as it's Record Store Day we thought it would be good to mention the independent music shop we used to get stuff from in East Grinstead. Like most local independent record shops it had a terrible, terrible name: Jingles. When we last went back to look for it — in 2008, just after it was announced that Woolworths would close — we discovered that it had closed down and was now a computer shop (above).

Jingles was great. It was more expensive than Woolworths so we'd buy our albums in Woolies (the idea of "supporting your local record store" by paying over the odds for music is something of a luxury many can't afford) but where Jingles really came into its own was with singles.

It seems inconceivable now in an era when singles are obsessively pored over and promoted and dissected by fans months in advance of release but in the 90s it was quite possible to walk into Jingles and find yourself confronted by stuff you had no idea was coming out. It seemed Jingles had everything in every genre and, as was the way those days, in both CD1 and CD2 editions. CD singles were ridiculously cheap, often 99p or £1.99.

To those who now seem to think that a fair price for music is nothing at all, 99p or £1.99 might seem like a lot of money, but in the 90s those prices seemed extraordinarily low. So low, in fact, that you could buy stuff you'd never heard of, let alone heard. On a trip to Jingles you could pick up something as unexpectedly good as this…

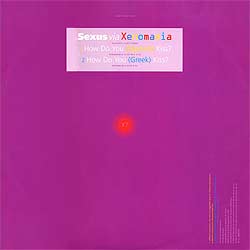

[youtube]hvTyKA9WIzE[/youtube] …or as unexpectedly bad as this. [youtube]5jZHwQipXPM[/youtube] As well as the CDs there were also big racks of vinyl. Not dusty 'ooh I'm in an indie record shop' boring vinyl, but brand new DJ promos and white labels of music that would often never end up being commercially released. Before Spotify, before iTunes, before you'd be able to hear everything somehow, it really felt that there would be things in those vinyl racks that could disappear forever if you didn't buy them.As we've mentioned before, one purchase we remember making at Jingles was a 12" club promo of a track called 'How Do You Kiss?' by ZTT-signed act Sexus. We'd bought one of Sexus' previous singles on CD and took a 99p chance on this promo, even though it wasn't the radio edit but instead was a remix by an outfit called Xenomania.

That purchase seems poignant now for two reasons: firstly, that mix was never eventually commercially released. We've just spent a few minutes searching online for it and the music is nowhere to be found, not on YouTube for example, and certainly in none of the legal download stores. If we want to hear the track we'll need to put that 12" on, and if we hadn't bought the record at that precise moment in time, we would probably never have heard it. Secondly, of course, there's the Xenomania link, not only interesting because 'Xenomania' went on to become XENOMANIA, but also because we've subsequently discovered that at that precise moment in time Brian Higgins was also living in East Grinstead, less than 90 seconds' walk from Jingles. He wrote Cher's 'Believe' — a song we also bought at Jingles — while living round the corner from the place.

That purchase seems poignant now for two reasons: firstly, that mix was never eventually commercially released. We've just spent a few minutes searching online for it and the music is nowhere to be found, not on YouTube for example, and certainly in none of the legal download stores. If we want to hear the track we'll need to put that 12" on, and if we hadn't bought the record at that precise moment in time, we would probably never have heard it. Secondly, of course, there's the Xenomania link, not only interesting because 'Xenomania' went on to become XENOMANIA, but also because we've subsequently discovered that at that precise moment in time Brian Higgins was also living in East Grinstead, less than 90 seconds' walk from Jingles. He wrote Cher's 'Believe' — a song we also bought at Jingles — while living round the corner from the place.

Once or twice they let us buy something that had been delivered on a

Saturday, even though it wasn't due on sale until Monday. Long before we

were lucky enough to be in the position where labels would send us

promos ahead of release, and even longer before pre-release downloads

(legal and otherwise) became the perceived norm for all music fans,

this 48-hour head start on the 'legal' release date seemed incredibly

exciting. Despite the inconvenience, and the expense and the mistakes, buying music really was exciting.

Slightly unusually in the world of the independent record shop, there

was no snobbery behind the counter at Jingles. We think the guys who

ran it might have

been local DJs, and we suppose that meant they prioritised what punters

really wanted over what they might have wanted punters to want. It may

simply have been that they liked loads of different music.

There used to be shops a bit like Jingles all around the world and now most, like Jingles, are different shops selling different things; it's pretty fitting, almost funny, that Jingles itself is now a computer store.

It's easy to get caught up in tedious nostalgia for formats, shops and habits from the past, and buying and discovering music online is obviously utterly brilliant and we wouldn't change it for a thing, but on a day when the world's music community focuses on sometimes inward-looking, rockist view of independent music retail it's important to remember that the most valuable local music shops were always the ones that ignored genre, loved music for music's sake and put their customers first.